Amy Carmichael was born in a small Irish village in County Down, modern-day Northern Ireland. Being the oldest of seven children in 1867, Amy saw her Presbyterian parents struggle to provide food, shelter, and education for the nine of them. Despite financial hardship, the Carmichaels were a family of faithful gratitude.

As a child, Amy hated her dark hair and eyes, and prayed that God would give her blonde hair and blue eyes instead. When the change she desired never took place, she wondered whether God really loved her. Years went by, and at the age of 15, Amy was taught the song “Jesus Loves Me.” She meditated on the words of the hymn, and it was then that the Holy Spirit worked in her heart, prompting her to give her life to Christ.

Years of financial hardship went by. When she was just 18, Amy’s father caught pneumonia and died, leaving a widowed mother to care for seven children. Refusing to give up hope, Amy started a weekly Bible study for the boys and girls of their village. When the family moved to Belfast for a better life, she noticed a need among the “shawlies.”

These “shawlies” were teenage girls working up to 14 hours a day in mills. Since they couldn’t afford hats, they could be identified by the shawls worn on their heads during winter. Amy visited the dangerous slums in which these girls lived, earning their friendship and trust. Soon, over 500 shawlies were meeting with her, overcrowding a small building. A miraculous donation of land from a mill-owner and funds from a fellow Christian resulted in the building of a meeting hall, now still standing as “Welcome Evangelical Church.”

But funds were still running out, and the Carmichaels moved to Manchester England in hopes of job opportunity. There, Amy became ill with neuralgia—a disorder that causes severe pain and weakness, confining patients to bed most of the time. Robert Wilson, a family friend, offered to move Amy to Cambria to heal and live with him in the country. He was an old man who had lost his own daughter to sickness. The two soon became very close and Amy often called him by the nickname “dear old man,” or D.O.M. for short.

During those two years, she attended Robert Wilson’s Christian convention where she heard Hudson Taylor speak about the Chinese mission field. This event prompted Amy to pursue missions abroad. She decided to work for Hudson Taylor’s organization, China Inland Mission (CIM) and began the training process.

After making this decision, Amy wrote to her mother, “My dearest Mother, have you given your child unreservedly to the Lord for whatever he wills? O may he strengthen you to say yes to him if he asks something which costs.”

Her mother replied:

“Yes, dearest Amy. He has lent you to me all these years. He only knows what a strength, comfort, and joy you have been to me. In sorrow he made you my staff and solace; in loneliness my more than child companion; and in gladness my right and merry-hearted sympathizer. So darling, when he asks you now to go away from within my reach, can I say nay? No. Amy, He is yours–you are his–to take you where he pleases and to use as he pleases. I can trust you to him and I do...all day He has helped me, and my heart unfailingly says, ‘Go ye.’”

With this blessing, Amy moved to London to continue her training. However, due to her continued poor health, CIM deemed her unsuitable for China. Undiscouraged, she joined the Church Missionary Society. It was this organization that sent Amy to Japan at age 24.

Amy and the “dear old man” said their goodbyes at the port. As the boat drifted down the coast, Robert followed for as long as he could, the two friends yelling scripture verses back and forth until they lost sight of each other. Here, Amy stayed in a cabin full of roaches and rats, cheerfully maintaining the mantra, “in everything, give thanks.”

Once in Japan, she would suffer from extreme culture shock. Rather than complain, Amy took this as an opportunity from God to grow in her reliance upon Him. One of these difficulties had to do with clothing. The other missionaries dressed in traditional Japanese kimono. At first, Amy resisted. The cold climate irritated her neuralgia, so she preferred warm western dress. This changed, however, while evangelizing in a hospital. She shared the Gospel with a sick woman who seemed close to understanding the Gospel. But when the patient noticed Amy’s fur gloves, it became such a distraction that the conversation was dismantled. After that, Amy vowed never to let something so small as comfort get in the way of the Good News of Christ.

After 15 months surviving the Japanese climate in a thin kimono and no gloves, the cold took its toll. Her illness increased, and doctors encouraged her to move somewhere warm. After seeing many come to Christ during her time in East Asia, she once again packed her bags.

Amy took a brief stint in Sri Lanka, before moving to Bangalore, India. It was now 1896, and she had reached her late 20s. Immediately, she began learning Tamil and traveled with other missionaries to nearby villages, sharing the Gospel.

One day, Amy was speaking publicly near a temple. A young temple girl named Preena heard the message as she collected water outside. Preena had been sold into temple-slavery by her mother and would soon be married to a temple god, cementing her life in prostitution. She saw the kindness in Amy and wondered what it was that made this foreigner different.

Preena decided to escape before her wedding but was soon caught. The captors branded her with a hot poker as punishment, but she managed to escape again, this time remembering the white woman who spoke of God’s love. When Amy found Preena at her door, she knew she’d be arrested for disrupting the Hindu temple practices, but how could she turn the girl away? Preena began living under the care of the mission.

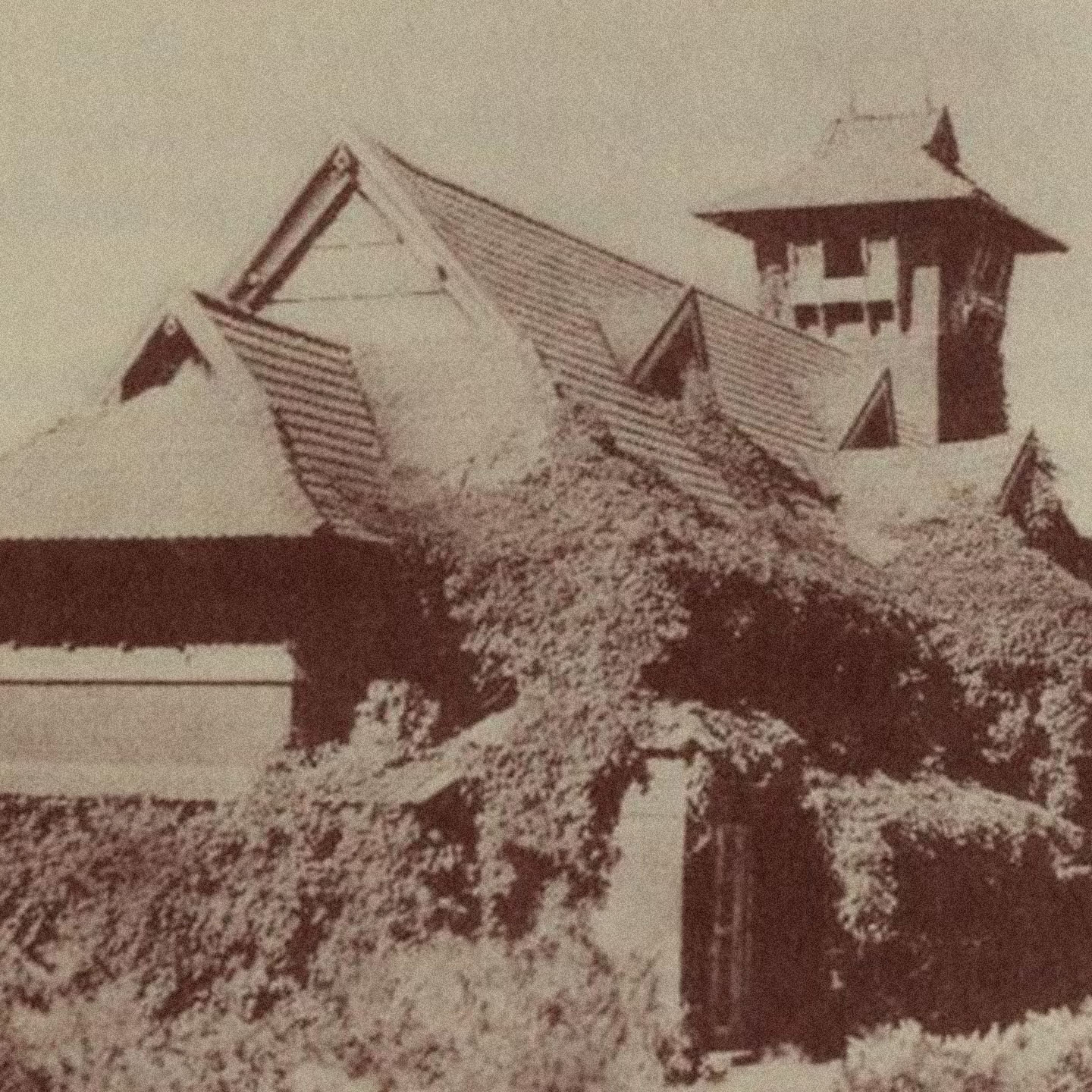

Preena’s story lit a passion within Amy. Many boys and girls were being sold into prostitution as temple-slaves, and in 1901, a rescued baby was brought to her. By 1904, 17 more children came under her care. She had never felt called to this kind of motherhood before, preferring to travel and evangelize, but she said, “It is not a servant’s business to decide which work is great, which is small, which is unimportant or important–he is not greater than his master.” With almost 20 children in tow, she founded the Dohnavur Fellowship for the care of children.

The following years were spent traveling to save children from temples. Amy dressed in a sari and dyed her skin with coffee to blend in undercover. Villages all around came to know her as “Amma,” meaning “mother.” Now she was grateful for her dark hair and eyes. Had God answered her young prayer, she never would have succeeded.

There was plenty to do at the fellowship. The harvest was plenty, but the laborers were scarce. Many wanted to help, but few lasted very long. In 1912, three other missionaries with whom Amy was very close died, leaving much grief and work in their wake. That same year, Amy got word that her mother had died as well.

She threw herself into the work, building schools and nurseries for children of all ages. She founded a hospital. The mission came to be well known for security and kindness, earning local trust and government support.

In 1931, while visiting another village in hopes of expanding their ministry there, Amy tripped and fell into a pit, breaking her leg, dislocating her ankle, and twisting her spine. This, in addition to her preexisting illness, left her bedridden for the rest of her life.

For the next 20 years, she directed the Fellowship from her bedroom, during which time she wrote many books and biographies, not only for herself, but for her fellow missionaries. This is the reason we can study her work today.

Amy Carmichael lived by example. She didn’t merely write about missions as an abstract philosophy from a cushy chair in a warm office. She had a servant’s heart, sacrificing her own well-being for the sake of others. She lived what she preached, preached far and wide, and gave us her stories and the stories of others for the sake of the Church.

In 1948, the Indian government outlawed temple slavery, which many credit to Amy’s influence. Three years later, in 1951, she asked that no grand monument be built in her honor before passing away at age 83. During her life, she’d saved over 1,000 children, 900 of which still lived at the Fellowship by the time of her death with 40-50 helpers. As news of her accomplishments reached Europe, people rejoiced in God’s use of a poor Irish girl. Today, a small bronze sculpture in Northern Ireland honors her work, and her grave in India is marked simply, “Amma.”

Additional Resources

- Watch our documentary on Amy Carmichael.

- Read Iain Murray's biography about her faithful life

- Read her own reflections on her life.