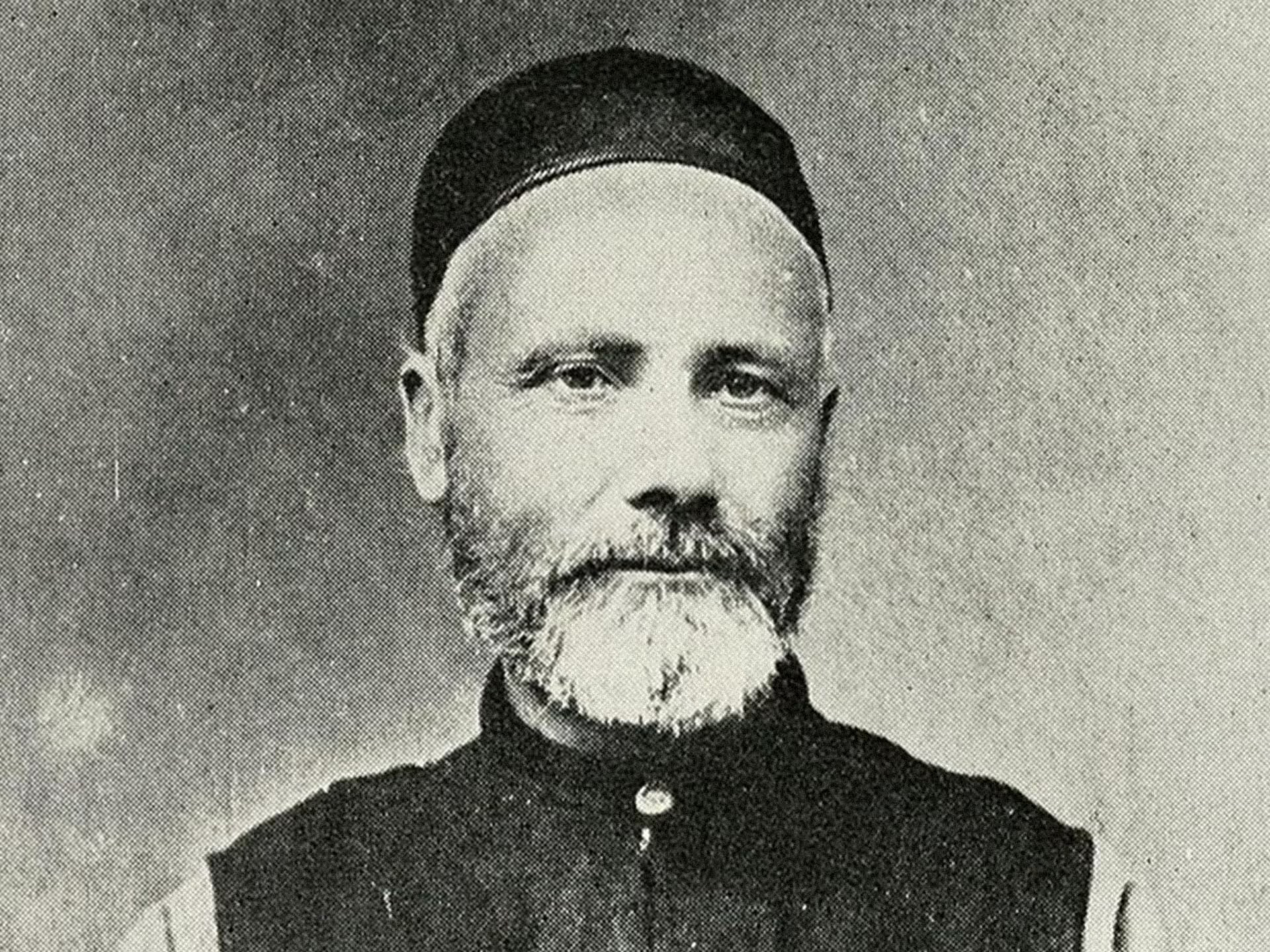

Gilmour’s Early Years

James Gilmour was born in Scotland in 1843 to James and Elizabeth Gilmour, the third of six sons. The Gilmour home practiced family worship every morning and evening, parents and grandparents intriguing the children with missionary tales.

He was converted to Christ while studying at the University of Glasgow and later surrendered to missionary service, in part because the needs abroad were greater than in his homeland. He said, “To me the soul of an Indian seemed as precious as the soul of an Englishman, and the gospel as much for the Chinese as for the European.” Following further studies, Gilmour joined the London Missionary Society and was ordained an evangelist to Mongolia. In 1870, just a few months before his 27th birthday, he sailed for Peking (modern day Beijing), the capital city of China.

Life in Mongolia

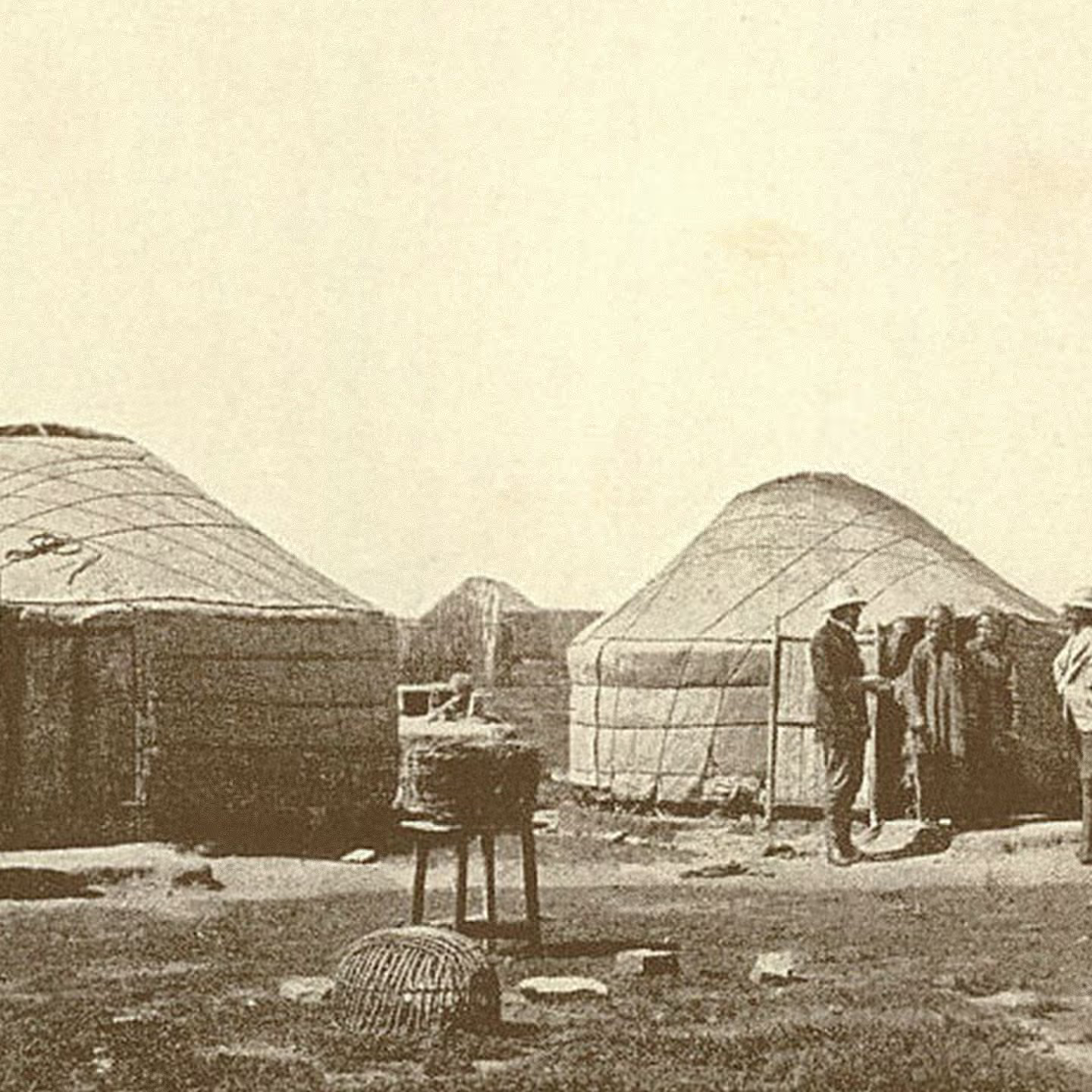

While a missionary in Mongolia, a land which followed the religion of Buddhism and had no understanding of Christianity, Gilmour modeled Christlike character like frugality, prayer, persistence, and fatherly care. But self-denial stands as the Mt. Everest mark of his life. He quickly and happily eschewed personal comfort. To reach the people, Gilmour became one of them. He learned their language. He wore Mongolian clothing. And, most practically, he lived the nomadic life.

Trials

Gilmour endured many hardships, especially in the early days. He struggled to cross the border because of passport issues. He didn’t know the language. Few showed him sympathy. He ministered alone. Apart from his tragically short marriage, he never enjoyed the privilege of a missionary teammate. His language teachers weren’t helpful. He suffered from loneliness and depression, even contemplating suicide. He wrote:

“I take this opportunity of declaring strongly that on all occasions two missionaries should go together. I was not of this opinion a few weeks ago, but I had no idea how weak an individual I am. My eyes have filled with tears frequently these last few days in spite of myself, and I do not wonder in the least that [a local trader’s] brother shot himself.”

After a stinging remark was made about his poor progress in the language, he got radical. He ventured into the open plains until he found a man willing to teach him blue-collar Mongolian. For several months he lived as a Mongolian in their huts to learn the language. The people loved him for this, but they struggled to understand Christian doctrine. They said things like: “If God is omnipresent, how can Jesus be sitting on the Father’s right hand?” Or, “If God is everywhere, does it mean he is also in the cooking pot? Will he be scalded?”

Because the Mission underfunded Gilmour, he walked hundreds of miles from place to place. He couldn’t afford a beast to ride upon. Beyond preaching the gospel, he printed small Christian books, which were far more attractive to the people than large Bibles. He also practiced dentistry and cured the diseases of the locals as best he could, though he was never formally trained.

Marriage

Gilmour desperately wanted a wife. One day while visiting friends in China, he happened to see the photo of a missionary wife’s sister, Emily Prankard. He immediately wrote to her proposing marriage. Friends laughed at him for such a rash decision. “What if you don’t like her,” they said. About a year later in December of 1847, James and Emily were married in Peking, China, having seen each other for the first time just a week earlier. The marriage proved to be a happy one. Emily was godly and sweet. Gilmour wrote of her: “She is a jolly girl, as much, perhaps more of a Christian and a Christian missionary than I am.”

His new wife adjusted well. During trips from Peking to Mongolia, Emily learned the language quickly. She also endured some strange Mongol customs, like their habit of free access to everyone’s tent—a challenge indeed for newlyweds! It was almost impossible to have private conversations.

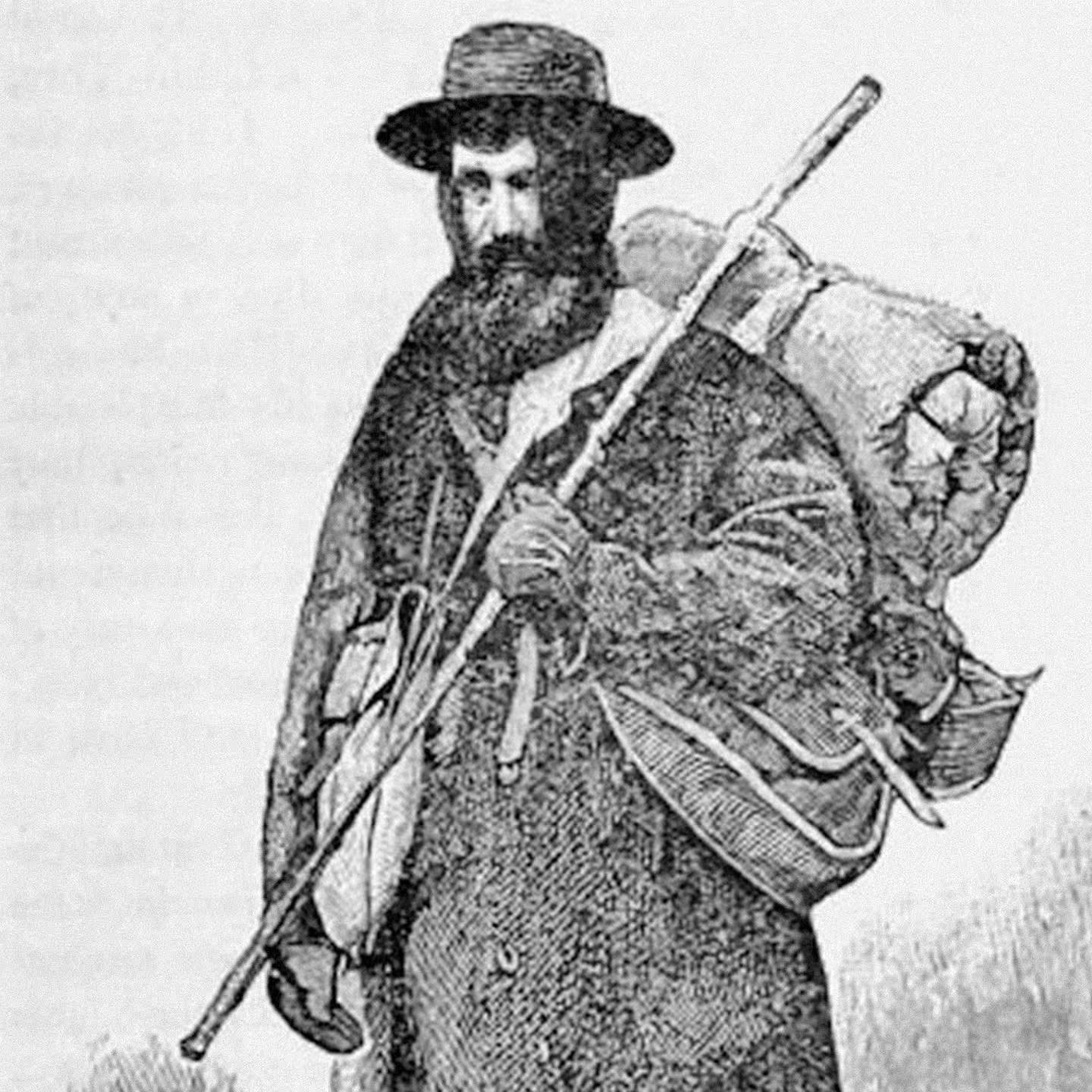

Final Years

Returning to China from furlough in 1884, Gilmour increased his treks to Mongolia. The Mongols were shocked a foreigner would walk like a poor man with all his belongings on his back. Some inns even turned him away because they thought he was a tramp. Then, one evening in a hut, Gilmour’s first convert professed Christ. Gilmour said in his journal it was as if those words “had been spoken by an angel from out of a cloud of glory.”

Sadly, Gilmour’s wife died soon thereafter, after eleven happy years of marriage. Yet, he remained in Mongolia, even when all thought he would quit.

Whisky, opium, and tobacco impoverished many of the Mongols. Gilmour rebuked them for wasting money, time, and land on such foolish exploits, as many of the Mongols lived in rags. He’d say: “Repent and cease this great waste.” The people sometimes asked for absurd and comical kinds of medical help. Gilmour recorded that “one man wants to be made clever, another to be made fat, another to be cured of insanity…another of hunger…most men want medicine to make their beards grow.”

His method rarely changed. After walking from the previous village, he set up his tent to dispense medicine to the sick, preach to sinners, sell books to the interested and distribute tracts to all that would take them. He kept meticulous records. In one 8-month trip to Mongolia, he saw over 5,700 patients, preached to over 27,000 people, sold over 3,000 books, distributed 4,500 tracts, and traveled (mostly on foot) nearly 2,000 miles. He wrote: “Out of all this there are only two men who have openly confessed Christ. In one sense it is a small result; in another sense there is much to be grateful for.”

Gilmour returned to China again after a two year furlough, but died of typhus fever on 21 May, 1891, a month after arriving. He was 47 years old.

Conclusion

While suffering in his early years, Gilmour wrote: “Comfort is not the missionary’s rule.” Just as Paul beat back his impulses for comfort, relaxation, and entertainment (1 Corinthians 9:25), so Gilmour resisted ease so that he might win souls to Christ, even if “success” had not been obtained.

To reach the people, Gilmour became one of them. He learned their language. He wore Mongolian clothing. And, most practically, he lived the nomadic life.

Additional Resources

- Read "Who was James Gilmour?" on Missionary.

- Read his diaries, letters, and reports.